A Lively French writer relates, that man having met the sheep wandering, like himself, upon the earth, caressed it, flattered it, and conducted it to his abode, sheltered it under a roof as rudely constructed as that which covered himself, carried it fresh grass for its food, and took care of it. But shortly, man demanded some milk of the sheep; soon after, he asked for a little wool; and, in the course of time, he killed it for its flesh. Having done all this, he melted down its fat to supply his lamp; and, finally, he wrote upon its skin.

The ancients seem to have substituted the skins of animals, for papyrus and other articles, as a writing material, from a remote period. The origin of parchment was due to necessity, the inventive parent of so many of the arts and conveniences of life; the stimulant of man’s ingenuity, when he suffers under present difficulties, or when he anticipates increased comfort and convenience. Some accounts refer the invention of parchment to a distant period, while others maintain that the date of its invention is altogether lost, amid the troubled waves of the broad ocean of distant time. According to the former, Eumenes attempted to found a library at Pergamus, about two hundred years B. C, which was to rival the celebrated Alexandrian library. One of the Ptolemies, a king of Egypt, jealous of the success of the rival library, and manifesting a spirit which, in modern times, would be thought pitiful and intolerant, made a decree, prohibiting the exportation of papyrus. The inhabitants of Pergamus, no longer being able to procure the material on which to transcribe the manuscripts to which their writers had access, adopted the skins of animals, prepared in a peculiar manner, as a substitute. They formed their library of this material, which was named after their city, Pergamena; whence also, it is supposed, we get our modern term parchment. The modern Germans and Italians, however, retain the original term: in the former language it is called Pergament, and in the latter Pergamena. The ancient Latins also applied the term membrana to parchment.

Some authorities, however, deny that parchment was first made at Pergamus; they state that the Hebrews had books written on the skins of animals in the time of David. According to Diodorus, the ancient Persians wrote all their records upon skins. It would appear, therefore, that King Eumenes was the improver, and not the inventor, of parchment. Dr. Prideaux imagines, that the authentic copy of the Law, which Hilkiah found-in the Temple, and sent to King Josiah, was written on parchment; because, he thinks, no other material could have been so durable as to last from the time of Moses till that period, viz. eight hundred and thirty years.’ But the Egyptians wrote on linen; which has been preserved on mummies for ages, and exists at the present day. It has, therefore, been suggested, that the copy of the Law of Moses might have been written on this material. At any rate, however, most of the ancient manuscripts which remain, are written on parchment; and bat few on the papyrus. Herodotus, however, who lived about four hundred and fifty years B. C, relates that the Ionians, from the earliest period, wrote upon goat and sheep skins, from which the hair had been scraped, without any other preparation.

Though the term roll occurs several times, yet parchment is not expressly mentioned more than once, and that by St. Paul (2 Tim. iv. 13), in the first age of the Christian era. Parchment seems to have been rather a scarce commodity until modern times. It was no uncommon thing, in the middle nges, to erase a beautiful poem, or a valuable history, merely for the sake of the parchment or vellum on which it is written. Many of the valuable writings of the ancients have been recovered from beneath a monkish effusion, or a superstitious legend, by carefully following the traces of the pen, or style, which had impressed the former performance upon the membrane; which traces had not been entirely obliterated by the second scribe. Persons who prepared parchment, by erasing a manuscript, were called “parchment restorers;” thus an old French writer says:—

Our parchment makers are very skilful. Our parchment restorers are not less so. Some parchment has been restored three or four times, and has successively received the verses of Virgil, the controversies of the Arians, the decrees against the books of Aristotle, and, finally, the books of Aristotle themselves.

Parchment is like an easy man, who is always of the same opinion as the last speaker.

The preparation of parchment is by no means a pleasant or cleanly operation. Our readers may, probably, have seen carts loaded with sheep-skins proceeding from large markets, or in the vicinity of slaughter-houses. These skins are bought of the butcher by the parchment-maker, in order to prepare, from them, the material in which he deals. The skins are first stripped of their wool, which is sold to the wool merchant, who prepares it for the making of cloth, &c. They are then smeared over with quick-lime on the fleshy side, folded once in the direction of their length, laid in heaps, and so left to ferment for ten or fifteen days.

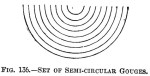

The skins are then washed, drained, and half-dried. A man called the skinner stretches the skin upon a wooden frame. This frame consists of four pieces of wood, mortised into each other at the four angles, and perforated lengthways from distance to distance, with holes furnished with wooden pins that may be turned like those of a violin. The skin is perforated with holes at the sides, and through every two holes a skewer is drawn : to this skewer a piece of string is tied, as also to the pins, which being turned equally, the skin is stretched tight over the frame. The flesh is now pared off with a sharp iron tool, which being done, the skin is moistened and powdered with fine chalk: then, with a piece of flat pumice-stone, the remainder of the flesh is scoured off. The iron tool is again passed over it, and it is again scoured with chalk and pumice-stone. The scraping with the iron tool is called draining; and the oftener this is done, the whiter becomes the skin. The wool or hair side of the skin is served in a similar manner; and the last operation of the skinner is to rub fine chalk over both sides of the skin with a piece of lambskin that has the wool on: this makes the skin smoother, and gives it a white down or knap. It is left to dry, and is removed from the frame by cutting it all round.

The parchment-maker now takes the skin thus prepared by the skinner. He employs two instruments; a sharp cutting tool, sharper and finer than the one employed by the skinner; and the summer, which is nothing more than a calf-skin well stretched upon a frame. The skin is fixed to the summer; and the parchment-maker then works with the sharp tool from the top to the bottom of the skin, and takes away about one half of its thickness. The skin being thus equally pared on both sides, it is well rubbed with pumice-stone. This operation is performed upon a kind of form, or bench, covered with a sack stuffed with flocks; and this process leaves the parchment fit for writing on.

The paring of the skin in its dry state upon the summer, is the most difficult process in the whole art of parchment-making; and is only entrusted to experienced hands. The summer sometimes consists of two skins, and then the second is called countersummer. The parings and clippings of the skin in the preparation of parchment are used in making glue and size.

…

Vellum is’a kind of parchment made from the skins of young calves: it is finer, whiter and smoother than common parchment, but prepared in the same manner, except that it is not passed through the lime pit.

Parchment is coloured for the purposes of binding, &c. The green dye is prepared from acetate of copper (verdigris), ground up with vinegar with the addition of a little sap green. Yellow dye is prepared from saffron; a transparent red from brazil wood ; blue from indigo, ground up with vinegar ; black from the sulphate of iron and solution of galls. Virgin parchment, which is thinner, finer, and whiter than any other kind, and used for fancy work, such as ladies’ fans, &c, is made of the skin of a very young lamb or kid.